Gas producers in the Permian are facing the prospect of severe transportation constraints over the next year or so before additional gas takeaway capacity comes online. Left unchecked, continued production growth could send gas at Waha spiraling to devastatingly low prices for producers. However, there are a number of ways producers and other industry stakeholders could mitigate the growing supply congestion in West Texas, at least in part, and possibly dodge the proverbial bullet. The longer-term solution will come in the form of new pipeline capacity, which will shift vast amounts of Permian gas east to the Gulf Coast and potentially create a new problem — supply congestion and price weakness along the Gulf Coast, at least until sufficient export capacity is built there to absorb the excess gas. Today, we wrap up our Permian gas blog series, with our analysis of how these events will unfold, including an outlook for Waha basis.

We took a closer look at the effects of rising production on outbound gas flows, pipeline utilization and prices. Gas flow data indicates that Permian outflows have increased in just about every direction, and pipeline utilization rates are at or near capacity (also see Omaha for more on changing flow patterns). As the pipes approached capacity limits in recent months, Permian gas prices took a hit, falling well below Henry Hub and other downstream pricing hubs. That pressure has eased in recent weeks as power demand kicked in for summer and exports to Mexico ticked up slightly. But that reprieve is likely to be temporary as long as Permian gas production continues growing and exhausting takeaway options.

To address the impending takeaway capacity shortage, midstreamers are scrambling to build new pipeline capacity from the Permian. As we detailed in Part 3, there are six publicly announced pipeline projects vying to relieve Permian constraints, all with routes that move gas east to where the demand is growing the most — at the Gulf Coast. Announcements for two of these — Enterprise and Energy Transfer Partners’ (ETP) recommissioning of their Old Ocean Pipeline (in conjunction with the expansion of their North Texas Pipeline, or NTP), and Williams’ Bluebonnet Express happened in just the past few weeks. Additionally, Tellurian has said that, based on supplier response, it’s moved up the target completion date for its Permian Global Access Pipeline (PGAP) to late 2021/early 2022, potentially a full year from its original target of late 2022. There also are at least another three “stealth” projects that we know of. So that makes at least nine projects that we’re aware of that, if they were all built, would add 16 Bcf/d of new capacity between late 2018 and 2021.

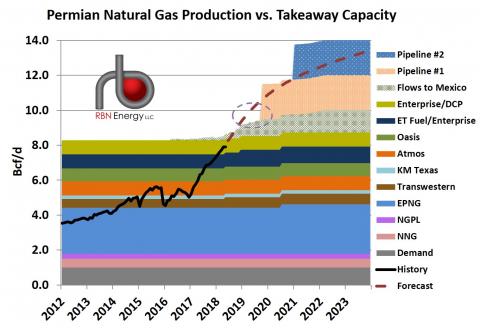

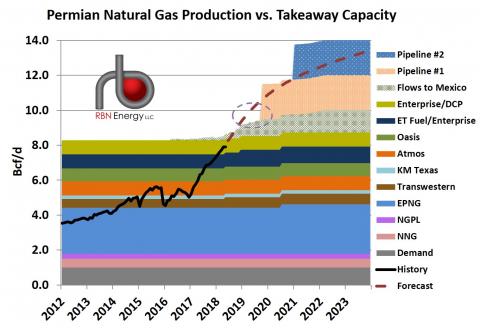

Today, we consider the price implications of near- and mid-term takeaway constraints before the first of these pipelines comes online, as well as the long-term effects of the new capacity as it gets built. To get a better sense of how the Permian gas market could evolve over the next five years, Figure 1 overlays current and forecasted production levels (black and red-dashed lines, respectively) on top of the takeaway stack (colored layers), which includes existing pipeline capacity, local demand and exports to Mexico (gray-mesh layer). This is the same stack graph we showed in Part 1, but this time it includes our production and takeaway capacity forecast.

Figure 1. Source: RBN Energy

The red-dashed line shows the production growth trajectory, assuming unfettered access to takeaway capacity. In this scenario, we estimate that volumes would reach more than 13 Bcf/d by 2023, an increase of 5.0 Bcf/d from just under 8.0 Bcf/d today. But the reality is that takeaway capacity is a limitation, and as the stacked graph illustrates, production growth at that pace would max out capacity (including demand and exports) by fall of this year. In contrast, the first big capacity addition — Pipeline #1 in the graph (peach polka-dotted layer) — is likely to be Kinder Morgan’s Gulf Coast Express (GCX), which isn’t due online until October 2019. That leaves a year gap (purple oval) when the Permian supply would be boxed in and Waha prices would come under tremendous pressure. Then, after getting some relief from Pipeline #1, capacity would get maxed out again in 2020 until the Pipeline #2 is built in early 2021 (blue polka-dotted layer), leaving open the risk for another year of severe constraints and heavy price discounts at Waha.

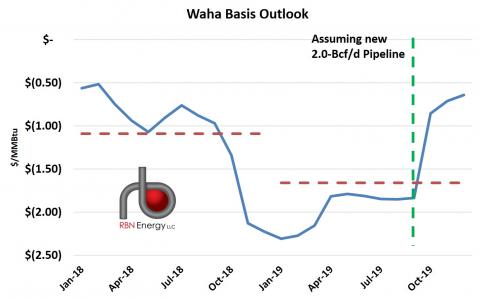

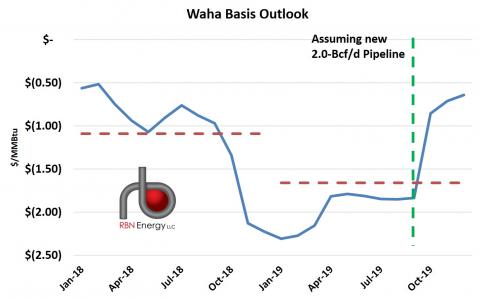

How bad could prices get? Based on the above timeline, our forecast in the RBN NATGAS Permian report, shown in Figure 2 below, projects that the Waha basis differential to Henry Hub, which has been whipsawing between 50 cents and $1.00/MMBtu below Henry, would blow out to a negative 2.25/MMBtu towards the end of the year when constraints are in full effect, and average about $1.00 under Henry for 2018 (red dashed line across 2018). By that estimate, the Permian cash price would average about 75 cents/MMBtu. Conditions would worsen in 2019, with average basis dropping to $1.60 under Henry (red dashed line across 2019). That happens even with the assumption that basis will improve in the fourth quarter of 2019, when a new 2.0-Bcf/d pipe comes online to relieve the constraint. Without the new pipe at that point, basis would not improve. Additionally, it’s worth noting, that prices could get even worse than that, considering that Permian gas production is associated gas, driven by crude oil economics; as long as the economics work for crude, even 75-cent/MMBtu gas may not slow down production growth.

Figure 2. RBN NATGAS Permian Report

But again, these are our projections assuming production grows unchecked and without substantive change on the takeaway capacity side of things. In practice, however, there are a number of steps that producers, marketers, and midstreamers could take when capacity becomes fully utilized to mitigate a basis meltdown while the market awaits more pipeline capacity:

Additional intrastate, brownfield pipeline projects could be announced that circumvent regulatory hoops and come online quicker. An example of this is the Old Ocean-NTP combo (also discussed in detail in Where Do We Go From Here). While these may offer up relatively small volumes — just 160 MMcf/d in the case of Old Ocean-NTP — it would provide some incremental outlet for the gas in the interim.

Producers could recover more ethane from the gas stream, leaving more room for dry gas on the takeaway pipelines. The economics of ethane recovery are improving, suggesting this could increasingly be a viable, if partial, relief valve for producers

If Waha supply prices get low enough, producers may opt to curtail less economical legacy dry gas production freeing up some of the takeaway capacity for more associated gas.

Producers or processors could flare excess gas to bide their time until new takeaway capacity comes online. Flaring was a big part of the answer for Bakken producers in North Dakota, though state regulations can be a limiting factor (see There’s a Fire in the Night). In the case of the Permian, the Texas Railroad Commission (TRRC) website says it issues flare permits for 45 days at a time, for a maximum limit of 180 days, while long-term flaring permits are a rarity. With flaring on the rise, the TRRC and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) are both looking at the issue, as the industry awaits more clarity.

Some producers also are looking into reinjection or gas disposal wells to sequester the gas until takeaway capacity becomes available. This is similar to what gas flood operations have done for years in order to increase pressure and enhance recovery from a well, or in the case of gas disposal wells, to dispose of produced water.

Increasingly, we also are hearing of producers with insufficient pipeline takeaway capacity simply considering temporarily moving their investment programs to other basins, such as the Eagle Ford for example, where takeaway capacity is not a problem. The expectation is that once additional pipeline infrastructure is built from the Permian, they can return and continue where they left off.

Finally, gas producers may get some relief through market forces disparate from gas. It is quite possible that crude oil production could slow down — due to its own takeaway constraints or if lower prices return. If crude oil production growth slows, the growth trajectory of the associated gas will slow as well. In fact, that may already be happening to some degree, as Permian gas volumes have flattened out in the past couple of months.

Any one or combination of these factors could help reign in the Permian’s gas production growth, which could, in turn, keep Waha basis from testing rock bottom in the meantime. So there’s the possibility that we may never see basis spiral to $2.00 discounts.

Eventually, of course, new takeaway pipelines will get built and provide basis relief to the Permian, setting off an entirely different chain of events in the market. Specifically, the new large-diameter pipelines will move sizable amounts of gas east to the Gulf Coast. The more gas that moves east, the more upside for Permian basis, but the more downside for downstream price hubs along the Gulf Coast, particularly given that, based on current timelines, the pipeline capacity and flows will outpace some of the liquefaction and export capacity on the demand end of the pipes.

Referring back to the project map and details in Part 3, of the six publicly announced takeaway projects, there are two projects totaling 4.0 Bcf/d of capacity that are destined for the Agua Dulce/Corpus Christi market area in South Texas, three others, including the Old Ocean-NTP combo, totaling another 4.0 Bcf/d or so to the Katy/Houston Ship Channel (HSC) market and one 2.0-Bcf/d pipe to southeastern Louisiana.

So, for example, if two pipes moving 4.0 Bcf/d are built into the Agua Dulce market by the end of 2019, but Corpus Christi LNG is adding just 1.4 Bcf/d of liquefaction/export capacity by then and exports to Mexico from South Texas are expected to grow less than 0.5 Bcf/d in that time, then that means a chunk of that Permian gas supply will be slamming the Gulf Coast before it’s needed. The result will be weaker basis at the Agua Dulce hub and a contraction of the price spread between Waha and Agua Dulce, at least until enough LNG and Mexico export capacity comes along to soak up the surplus. Two new pipes to Katy/HSC would have the same effect on pricing at those hubs based on the timing and scale of Freeport LNG’s liquefaction project.

So the bottom line is that the new Permian takeaway capacity will ultimately shift the supply congestion and price weakness from Waha to the South/East Texas region. This is where Tellurian’s PGAP project — the one making a beeline for southeast Louisiana — will provide an advantage, as it plans to bypass that Texas Gulf Coast congestion and deliver into the Louisiana LNG export terminals, albeit at a somewhat higher cost.

In the long run, the new pipeline capacity will help balance the Permian and overall Texas markets, but in the short term, we can expect some volatility as the oversupply pressure builds and producers work out their strategy to weather these conditions. If they effectively mitigate even some of the congestion, the market may just avoid a complete price collapse, but either way, the Permian market is in for a rough ride over the next year or so. How exactly this all shakes out will become clearer in the coming months, and you can bet that we at RBN will be updating this story along the way in the blogosphere.

https://rbnenergy.com/blame-it-on-texas-natural-gas-basis-implications-of-permian-production-and-takeaway-capacity